|

Jesus Christ

He called by to ask questions: ‘Did you ever punch a nose? Maybe a glancing blow, fourteen years ago? To dry-run the feeling?’

I wanted this man on my side. He had access to )**£!...><%^!. He seemed no more than the apron of a face, a way of looking.

You could say he had the veneer of a ladies’ man in the smash-up of his career. A man, or a desolate landscape. A trampled-on forest. Yet still, strangely attractive. Death overwhelms even mediocricity.

Why must it always end this way? ‘The face is the only avant garde we have’, I replied. ‘And a name. A good name is promotable.’

Jesucristo

Pasó a verme para realizar preguntas: “¿Alguna vez golpeaste una nariz? Quizá un golpe de refilón, hace catorce años? ¿Para hacer la prueba con la sensación?”

Quería que este hombre estuviera de mi lado. Él tenía acceso al )**£!...><%^!. Parecía nada más que el delantal de un rostro, una manera de mirar.

Podría decirse que tenía el chapado de un don juan en el retrizamiento de su carrera. Un hombre, o un paraje desierto. Un bosque pisoteado. Y sin embargo, extrañamente atractivo. La muerte agobia incluso a la mediocridad.

¿Por qué siempre ha de terminar de este modo? “El rostro es la única vanguardia que tenemos”, repliqué. “Y el nombre. Un buen nombre es promocionable”.

Although You Do Not Know Me, My Name is Patricia

For the record, we are undertaking research into Love, or Something Similar Fabricated in the Back Workshops of Imagination.

Clare, my assistant, is sorry she couldn’t be here, by the way. I, too, am sorry she couldn’t fit through your bathroom window, even when naked. ‘Now pass me back my knicks and cash and let me go refine some statistics!’ Beneath the streetlights, her sweat glands recalled the margarine in my carrier bag. Having lubricated my surfaces, I slithered through the chink, alighting on your cabinet.

From your array of dyspepsia remedies, I deduce that you are a communist academic and your wife a neophite Bohemian. Although Flossie was never exactly a cabaret dancer, she demanded to be called Flossie and was in a panic to marry. Panic and relentless love are easily mistaken.

Claire would say your miniature soap collection belies a marriage of sex and pecuniary convenience. Heaps of sex. Every night for a month, then every other night for two months. Soon it was three times a week for a year, then once a week. Now, almost never. Don’t worry though, the future is broken anyway. Something went wrong a while back. Why else would we huddle together in cities, if not to feel better (if not safe exactly)?

We make up for it by making things up, spilling our adventures to anyone who’ll listen. Some share life, like two unequal halves of a Chelsea Bun, with a stranger. Some release the sugared non-half into the mouth of a stranger. Some realise the unequal-half-fiddle once the sugar’s all swallowed by a mouth that won’t be around forever. The inventions of the back workshop may be high-spot along the damp bricks of years, Claire would deduce, if Claire could be here.

Aunque no me conoces, mi nombre es Patricia

Para que conste, estamos realizando una investigación sobre el Amor o Algo Similar Fabricado en los Talleres al Fondo de la Imaginación.

Claire, mi asistente, lamenta no haber podido estar aquí, por cierto. Yo, también, lamento que no cupiera por la ventana de tu baño, ni siquiera desnuda. “Ahora regrésame mis calzones y efectivo y déjame ir a refinar mis estadísticas!” Bajo las luces de la calle, sus glándulas sudoríparas recordaron la margarina en mi bolsa de la compra. Habiendo lubricado mis superficies, me escurrí por el tintineo, bajándome en tu gabinete.

Según tu colección de remedios contra la dispepsia, deduzco que eres un académico comunista y tu esposa una bohemia neófita. Aunque Flossie nunca fue exactamente una bailarina de cabaret, exigía que le dijeran Flossie y tenía una prisa pavorosa por casarse. La prisa y el amor implacable se confunden fácilmente.

Claire diría que tu colección de jabones miniatura contradice un matrimonio de sexo y conveniencia pecuniaria. Un montón de sexo. Todas las noches por un mes, luego una noche sí y otra no por dos meses. Pronto fue tres veces por semana durante un año, luego una vez por semana. Ahora, casi nunca. Pero no te preocupes, el futuro está roto de todas formas. Algo salió mal hace mucho. ¿Por qué otro motivo nos apiñaríamos en las ciudades, si no es para sentirnos mejor (aunque no exactamente seguros)?

Despertamos para eso inventando cosas, divulgando nuestras aventuras ante quien se digne a escuchar. Algunos comparten la vida, como dos mitades desiguales de un Bolillo Chelsea, con un extraño. Algunos liberan la azucarada no-mitad en la boca de un extraño. Algunos se dan cuenta de que el medio-violín-desigual, una vez que el azúcar haya sido toda tragada por una boca, no estará ahí por siempre. Las invenciones del taller al fondo pueden ser el punto alto sobre los húmedos ladrillos de los años, Claire deduciría, si Claire hubiera podido estar aquí.

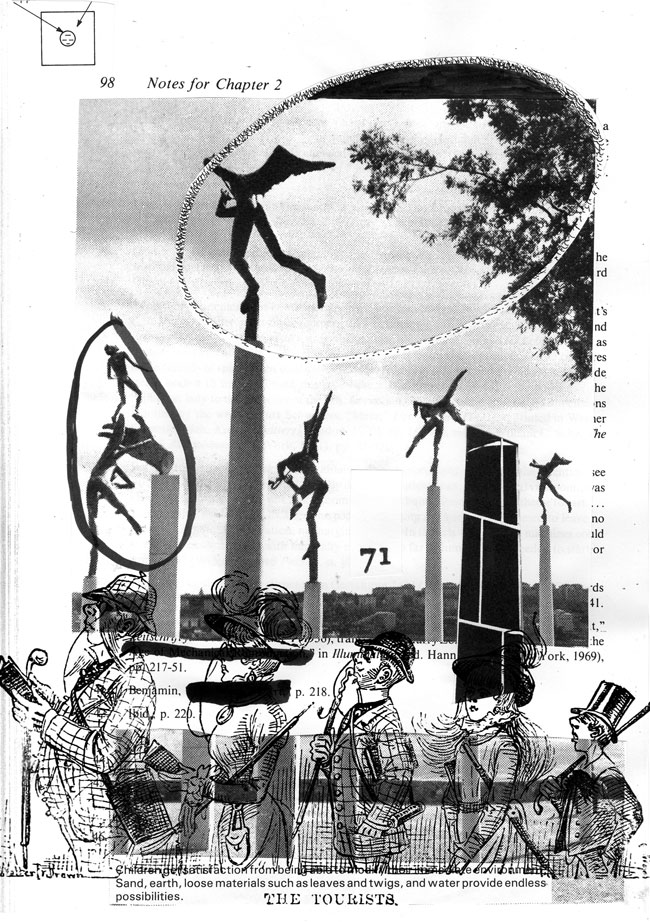

Le Parc

Every fifth Tuesday of the month my grandfather would meet with Monsieur Duchamp in le jardin public. Et voilà! Marcel digressed by the weeping beech tree. The hanging branches touched the ground. Being an artist, he said in squeezed English as he probed the foliage, is like crawling on your hands and knees along a narrow tunnel just to wash your filthy hands in the sink at the end of it, and then spending the rest of your life trying to get out backwards. A nut in a husk hit the soil. At any time though, my grandfather observed, one might be hauled out by one’s ankles.

Le Parc

Cada quinto martes del mes mi abuelo se reunía con Monsieur Duchamp en le jardin public. Et voilà! Marcel divagaba junto al abedul llorón. Las ramas colgantes tocaban el suelo. Ser artista, dijo en inglés apretado mientras sondeaba el follaje, es como andar a gatas por un túnel estrecho tan sólo para lavarte las manos asquerosas al final de él, y luego pasar el resto de tu vida tratando de salir en reversa. Una nuez en una cáscara cayó al suelo. En cualquier momento, sin embargo, observó mi abuelo, uno podría ser jalado hacia afuera por los tobillos.

|

|

Foto: Jamie Hawkesworth

Poemas publicados originalmente en Instant-flex 718 (Bloodaxe, 2013). Reproducidos con el permiso de la editorial.

Heather Phillipson. Trabaja con video, escultura, dibujo, música, texto y eventos en vivo. Durante 2015 ha presentado proyectos individuales en la Bienal de Estambul, Performa New York, Sheffield Doc Fest, Opening Times (otdac.org) y Schirn Frankfurt. Ha sido escritora-residente en Whitechapel Gallery así como artista-residente en Wysing Arts Centre, realizado numerosas exposiciones individuales y publicado tres libros de poesía: un panfleto con Faber & Faber en 2009; NOT AN ESSAY (Penned in the Margins, 2012); e Instant-flex 718 (Bloodaxe, 2013), el cual fue finalista del 2013 Fenton Aldeburgh First Collection Prize y del Michael Murphy Memorial Prize. Heather Phillipson. Trabaja con video, escultura, dibujo, música, texto y eventos en vivo. Durante 2015 ha presentado proyectos individuales en la Bienal de Estambul, Performa New York, Sheffield Doc Fest, Opening Times (otdac.org) y Schirn Frankfurt. Ha sido escritora-residente en Whitechapel Gallery así como artista-residente en Wysing Arts Centre, realizado numerosas exposiciones individuales y publicado tres libros de poesía: un panfleto con Faber & Faber en 2009; NOT AN ESSAY (Penned in the Margins, 2012); e Instant-flex 718 (Bloodaxe, 2013), el cual fue finalista del 2013 Fenton Aldeburgh First Collection Prize y del Michael Murphy Memorial Prize.

Foto: Jamie Hawkesworth.

|